Going through my life, I never expected to witness such rapid advancements in technology. Growing up in a home where my only access to the internet was the family computer shared between me and the rest in my household, the idea of robots and artificial intelligence invading the everyday was dystopian to me. Now, AI is practically inescapable.

Since entering community college back in 2020, both mine and my classmates’ workflows have drastically changed. I went from learning how to write essays and painstakingly correcting all grammatical errors by hand, to writing my ideas down as best I could before throwing my paragraphs into Grammarly, asking it to do 99% of the corrections for me. While this has helped me immensely without compromising my academic integrity, I don’t know if I can say the same thing for my peers.

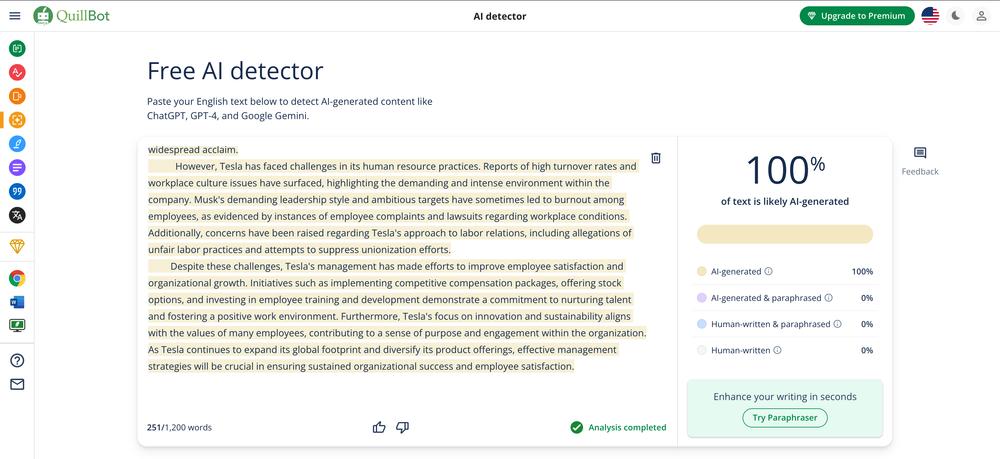

This past Spring semester, I was assigned three group projects by three separate professors. Two out of the three said that we could use ChatGPT if we cited it correctly, the other professor made no mention of ChatGPT in our assignment sheet. In one of the two pro-ChatGPT projects, I had two classmates turn in AI-generated content into our shared document. Had this happened a year ago, I likely would have overlooked their work, and so would have most professors. But since the letters “AI” are the two most popular letters of 2024, I spotted their attempt to get out of actually contributing to my group’s project, and immediately deleted it, then told them that they needed to completely rewrite their work.

You might be asking, “Gavin, you said that this was a pro-ChatGPT group project… why did you make them rewrite their work?” You see, the pro-ChatGPT group project still had limits to how we use it. The main reason we could use ChatGPT (for the most part) was due to it being a source of information, just like any other source you would find on the internet, but you had to cite it correctly in the report. In fact, the official APA Style Blog has a page dedicated to showing people how to cite ChatGPT in essays.

What my classmates seemed to do was feed ChatGPT a portion of our outline (which said classmates didn’t contribute to) and ask it to either summarize or write a paragraph about it, before promptly copying and pasting that text into our report. For those who have not written an academic paper in many years, that would be considered plagiarism, and would, at minimum, give my group an F for that project.

After going through the headache of essentially baby-sitting my lazy groupmates over the span of a month, I initially became frustrated over their selfishness and shortsightedness before remembering just how widespread this problem is at my college campus. Nearly every class I walked into, there were a handful of people ignoring the lecture occurring in front of them to work on other class assignments, and most of those people had one window open with either ChatGPT, Chegg, or Quizlet, alongside their online homework.

This cheating problem is so widespread, that the University of Nevada in Reno even found that over 50% of students cheat in college, and that’s likely just those that admit to cheating or get caught. In that same article, they mention some ways of reducing the amount of students that cheat, and while I do think such measures should be implemented in every college campus, I don’t think that is the end-all-be-all.

After transferring to the University of Texas at Dallas, I realized why so many students fall into acceptance of cheating as a form of completing work; taking any more than five classes over one semester is nearly impossible to do well. I’ve now completed 10 classes over the span of a year without cheating, and both semesters were exhausting while leaving little room for me to enjoy life outside of school. That’s not a sustainable way to live life for four years, even as a young adult.

2024’s Spring semester showed me not just how widespread cheating is, but also how professors can create a fun learning environment, prevent cheating, and give students time to enjoy life outside school. In my Business Law class, we were assigned 2-3 chapters of our textbook to read each week with four tests that made up our total grade. Each test was created by the professor from scratch and was based on what we discussed in class, anything from lawsuits against the show “Love Is Blind” to bickering over lottery winnings between two people divorced from a past relationship.

Not only did these topics make the class interesting, but the fact that each test was created by hand and differed from semester to semester likely prevented many students from attempting to cheat. From my experience, each test wasn’t terribly difficult, as long as you paid attention in class and did the readings outside of class (which usually took about an hour or two per chapter). This is how I think every class should be structured, as it checks all the boxes of a good class with good vibes.

The challenge that many other professors run up against is their traditional approaches to combating the cheating problem. Many other professors will overload students with work, essentially stuffing so much information into a single class in hopes that those students that cheat can at least learn a thing or two. This, to me, deters students from enjoying a class and makes college look like a waste of time compared to learning through experience. Professors need to put in the work into finding new and creative ways to deter students from cheating, as the traditional models don’t seem to do enough.

In my eyes, many professors don’t try to understand why students are cheating before they try to mitigate cheating. There needs to be some room for open discussions that allow professors and students the opportunity to discuss the topic of cheating without punishment looming over their heads. Right now, the cheating problem is taken from an “us versus them” perspective while the proper solution to cheating needs to come from a place of care and understanding for the students. If universities really care about their student’s success, then there needs to be some reformation in the university’s policies, with students’ help; only then can we start the process of collaborating over competing.